Introduction: The Frustration of the “Wrong” Choice

You’ve designed the perfect drill. The cones are set, the objective is clear, and the session plan is a work of art. You run the drill, and an athlete makes a move that seems completely unexpected – a seemingly “wrong” choice that goes against the obvious solution. It’s a common frustration for any coach, a puzzle of athlete agency and decision-making that can leave you wondering, “What were they thinking?”

But what if the answer doesn’t lie entirely within the athlete’s mind? What if the key is in the subtle “pulls” and “pushes” of the training environment itself? The emerging idea from ecological psychology is that the spaces we create do more than just present possibilities for action – they can be powerful invitations.

This post will explore a few counter-intuitive takeaways from this field that can fundamentally change how you design training sessions and understand the choices your athletes make.

1. Takeaway One: Your Environment Doesn’t Just Allow Action—It Solicits It.

The foundational concept here is the “affordance,” a term coined by psychologist James J. Gibson. An affordance is simply an opportunity for action that the environment offers an individual. A floor affords walking, a ball affordsthrowing, and an open space affords running. For Gibson, these affordances are permanent ecological facts; they exist whether the athlete perceives them or not. His key point was that affordances make behavior possible, but they don’t cause it. The environment is a landscape of opportunities, not a set of triggers.

However, recent thinking argues that affordances are rarely neutral. Some can actively “invite” or “solicit” certain behaviors. This doesn’t mean every possibility is an invitation. An environment offers countless affordances, but only a few may be strong enough to actively solicit a response.

This idea of a soliciting environment echoes an earlier concept from Gestalt psychologist Kurt Koffka, who wrote in 1935 that the environment has a “demand character”: “a fruit says, ‘Eat me’; water says, ‘Drink me’; thunder says, ‘Fear me’, and woman says, ‘Love me’.”

While inspiring, it’s crucial to understand where Gibson disagreed with this view. For Koffka, an object’s “demand” depended on an individual’s current needs – a mailbox only “demands” you use it if you want to post a letter. For Gibson, the affordance is an ecological fact that exists permanently, independent of the observer’s motivational state. The mailbox always affords posting a letter, even if you have nothing to send. The “invitation” is a property of the athlete-environment relationship, not just a feeling in the athlete’s head.

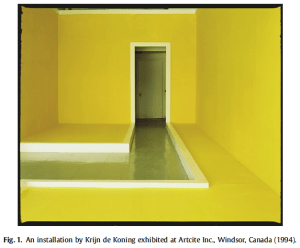

Consider the art installation by Krijn de Koning pictured in the figure here. This space affords an infinite number of actions: you could sit on the floor, touch the walls, or turn in circles. Yet, the specific configuration of planes creates a path that powerfully invites the vast majority of people to follow it and walk through the door. The design itself is sending a strong suggestion. This artist acted as an architect of movement, and as a coach, so do you.

The next time you set up a drill, don’t just look at it. Physically walk through it as if you were the athlete for the first time. What path of least resistance feels most inviting? What actions are being subtly suggested by the placement of every cone and teammate?

2. Takeaway Two: The “Strength” of an Invitation Depends on More Than Just Physical Ability.

Even if two athletes have identical physical capabilities, they might respond differently to the same environmental invitation. This is because the inviting character of an affordance isn’t just about what’s physically possible. An architect must understand their materials; a coach must understand these four factors that shape an invitation’s strength.

- Effort and “Optimal Fit”: Researcher Bill Warren made a useful distinction between “critical points” and “optimal points.” An action close to an athlete’s physical limit (a critical point) is unlikely to feel inviting. A drill that is overwhelmingly difficult won’t invite exploration. In contrast, an affordance that represents an “optimal point” – a “best fit” where minimum energy yields maximum effect- is highly inviting. An optimally challenging task naturally pulls the athlete in. This is critical, because an athlete is far more likely to unreflectively ‘give in’ to an environmental demand when that demand aligns with an optimal point – it’s the path of maximum efficiency.

- Culture: The culture of a sport or team shapes how athletes respond to affordances. A chair affords many actions – standing on it, putting a book on it – but culturally, its primary invitation is to be sat upon. In sport, this is even more pronounced. In a possession-focused soccer team’s culture, a tight passing lane ‘invites’ a safe pass, while in a direct, counter-attacking culture, the same space ‘invites’ a risky through-ball. The physical space is identical, but the team’s culture changes the nature of the invitation.

- Personal History: An individual’s past experiences are critical. An athlete who has previously been injured while making a sharp cut may be “repelled” by an affordance for that same movement, even if they are physically capable. The invitation to cut is silenced by past negative experience. Conversely, an athlete who has found great success with a specific move will feel a stronger invitation to use it when the opportunity arises.

- Survival Instincts: Some invitations are powerful because they tap into deep-seated, evolutionary pressures. An affordance that looks like a collision risk will powerfully repel an athlete, while an open lane to a goal will powerfully invite them. These instincts are so strong they can often override a coach’s specific instruction, as the athlete’s system prioritises survival and opportunity.

To design effective training, you must understand the athlete holistically. Their skill level, personal history, survival instincts, and the culture they train in all combine to tune how they perceive the “invitations” you build into a drill.

3. Takeaway Three: Agency Isn’t in the Head, It’s in the Athlete-Environment System.

The common view of agency is that it’s a form of “self-control” – a deliberate, internal decision-making process where an athlete consciously weighs their options and chooses one. We see a “bad” decision and assume a flaw in that internal calculation.

The ecological perspective offers a radical alternative. If affordances can invite action, then agency isn’t something that happens solely inside an athlete’s head. It emerges from the constant, dynamic interaction between the athlete and their environment. The behaviour we see is often a direct result of the athlete being “attracted or repelled” by the affordances you’ve placed around them.

Crucially, athletes often respond to these environmental solicitations unreflectively. They don’t stop and think; they act. As philosophers Dreyfus and Kelly describe it:

“In responding to the environment this way we feel ourselves giving in to its demands.”

This perspective completely reframes how a coach should view errors. A “bad decision” might not be a failure of the athlete’s mental processing. It could be a perfectly logical and unreflective response to a powerful – but unintended – invitation that you, the coach, designed into the drill.

However, this does not mean athletes are robots. It is essential to remember that an invitation can always be declined. While athletes may unreflectively respond to the strongest pulls from their environment, agency is retained. An invitation is not a cause. The question then becomes: Did the drill create such a powerful invitation to fail that it required a conscious, effortful decision from the athlete to overcome it?

Conclusion: From a Designer of Drills to an Architect of Invitations

This shift in thinking moves us from seeing the environment as a neutral stage for action to understanding it as a dynamic landscape of active invitations that solicit behavior. It changes the role of the coach in a profound way.

Your job is to make the invitation for the ‘right’ action so loud and clear that it becomes the most natural, unthinking choice for your athletes, while making the ‘wrong’ action feel awkward and inefficient. You are not just a designer of drills; you are an architect of invitations.

The next time an athlete makes an unexpected move, pause. Instead of asking, “What were you thinking?”, perhaps the better question is, “What did the environment invite you to do?”